| Schema | Profile | Identification | Membership Criteria (Exclusionism) | Pride | Hubris |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Week 11

Europe’s Far Right

SOCI 229

Lecture I: November 11th

Reminders

Response Memo Deadline

Your seventh response memo—which has to be between 250-400 words and posted on our Moodle Discussion Board—is due by 8:00 PM on Wednesday …

Unless …

… you attend the first Cummings Lecture this Wednesday.

Reminders

The Cummings Lecture

Title

Place, Polarization, and the Future of America’s Political Divisions

Abstract

Click to Expand or Close

Note: Scroll to read entire abstract.

How does place shape America’s polarized politics? Decades of political-economic transformations have reshaped both the kinds of people and the kinds of places that give their support to the Democratic and Republican Parties, hardening political boundaries along lines of race, class, religion, and context. Working-class, ex-urban, and industrial communities that were once the bedrock of the Democratic Party are now the sites of greatest contestation every election cycle, while the affluent suburbs that once fomented conservative activism in the 1950s and 60s are the sites of greatest growth for the Democratic Party. In this talk, sociologist Stephanie Ternullo (Harvard University) will consider the historical causes and contemporary consequences of these shifts in political geography, and the challenges they present for political representation in American elections, including the November 5th presidential election.

Date and Time

Location

Reminders

Dr. Stephanie Ternullo will be joining us before her talk.

Reminders

Final Paper Proposal

Final Paper Proposal Deadline

Your final paper proposals are due by 8:00 PM on Friday, November 22nd.

Reminders

Final Paper Proposal

Guidelines for the final paper proposal can be found here.

Reminders

Final Paper Proposal

To submit your final paper proposal, click here.

Sidebar—

A Few More Reflections on the 2024 Presidential Election

Once Again—Let the Dust Settle

Once Again—Let the Dust Settle

Working hypotheses are necessary. However, we have to embrace uncertainty and the possibility that our initial hunches are wrong. Falsification is simply not possible in the wake of an election.

Some (Potentially) Useful Charts

Some (Potentially) Useful Charts

Some (Potentially) Useful Charts

A Few Basic Takes

Material economic conditions matter.

A Few Basic Takes

Cultural contestation matters, too.

A Few Basic Takes

A Few Basic Takes

Moreover, exit polls—as noted last week—can be very misleading.

A Few Basic Takes

Worse, they can foment groupism (see Brubaker, Loveman, and Stamatov 2004) and its analytic corollaries: reification, essentialization, homogenization and so on.

A Few Basic Takes

This can lead to faulty inferences and spurious conclusions.

Moving Across the Pond—

Far Right Parties in Europe

by Matt Golder

First, Some Context

When Golder (2016) penned his review article less than a decade ago, the European far right was—on balance—a marginal player in the sphere of electoral politics.

First, Some Context

This is no longer the case.

First, Some Context

First, Some Context

Note

The infogram uses the term hard right in lieu of far right.

Let’s not do that.

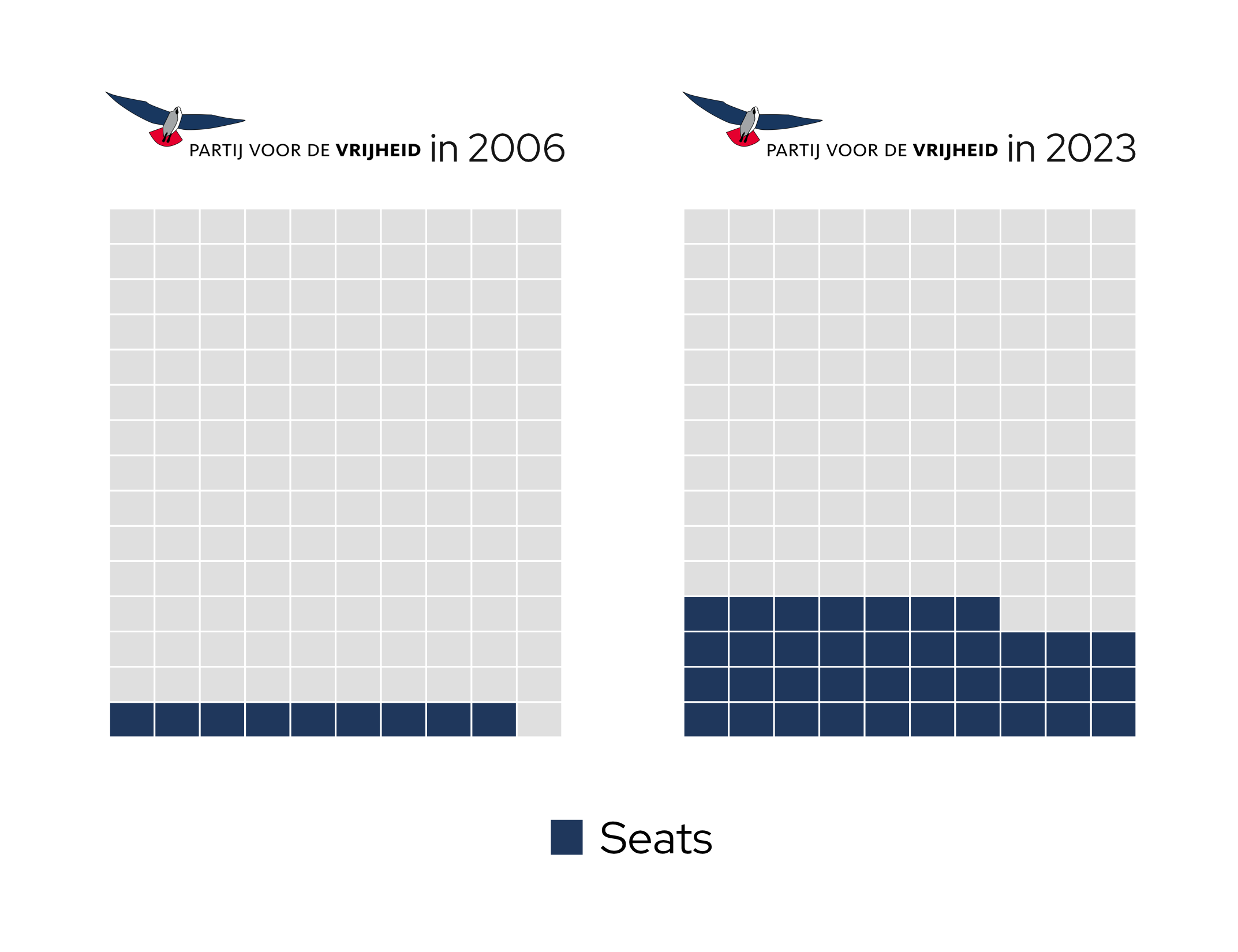

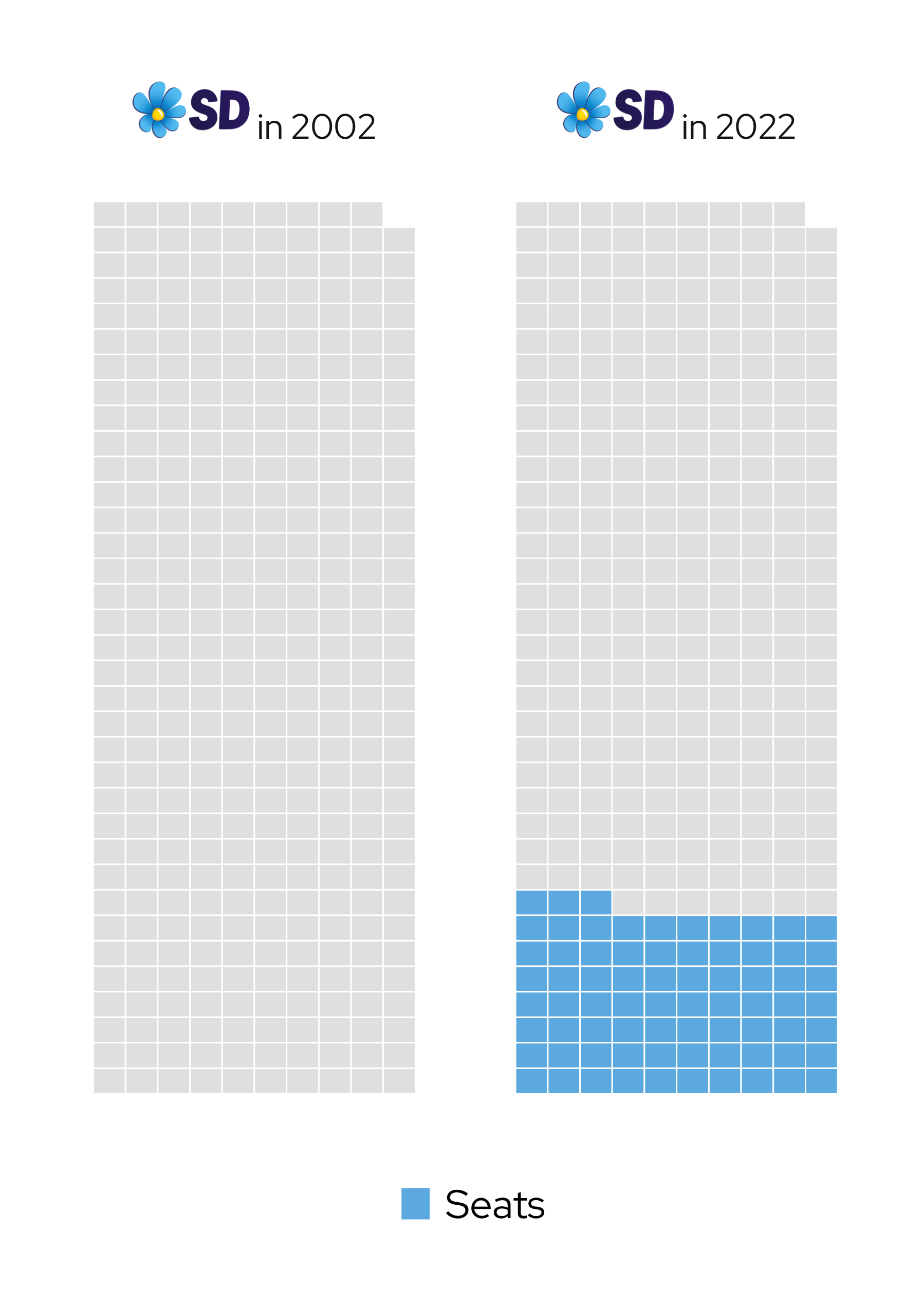

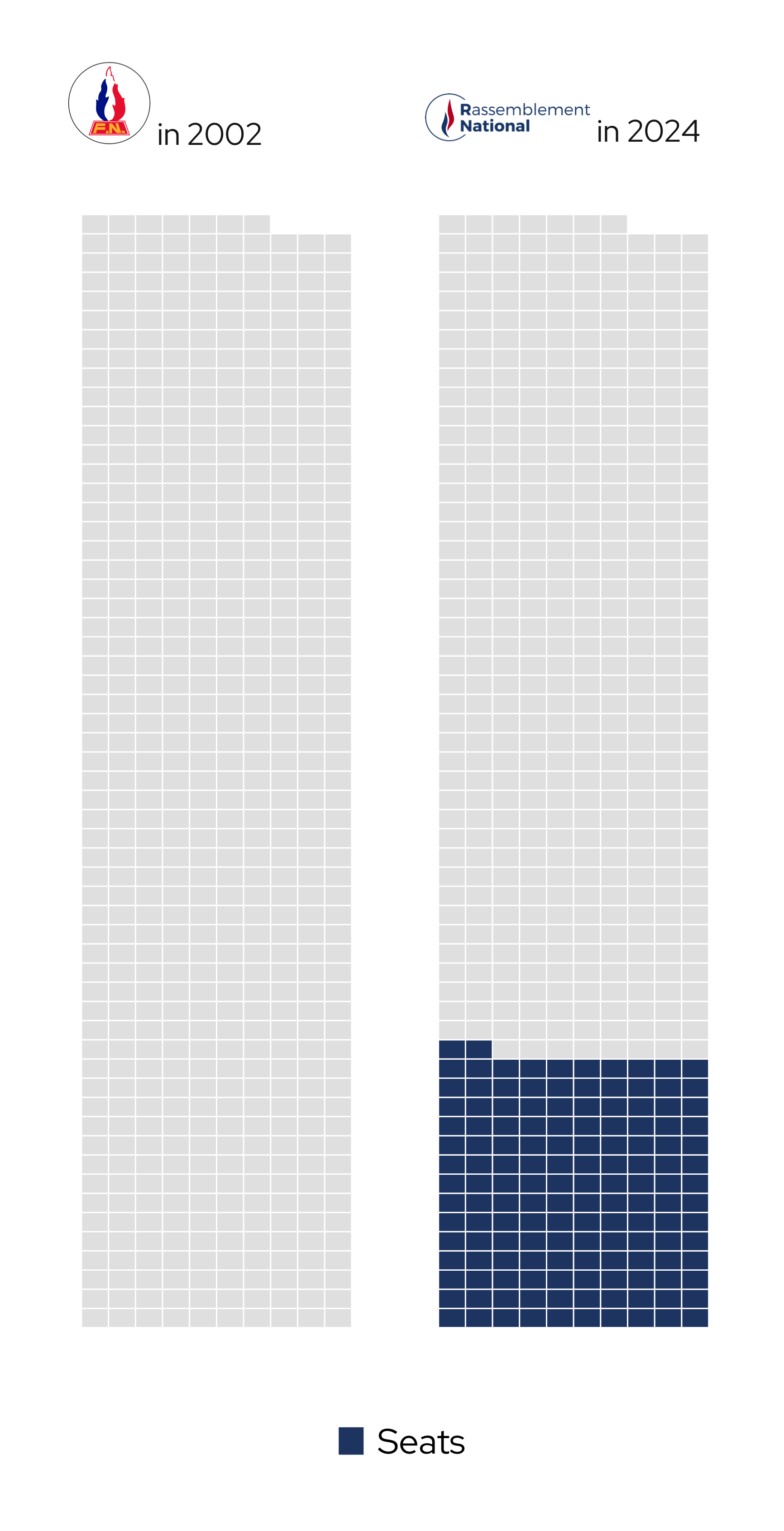

Now, Some Brief Case Studies

The Netherlands

Click to Expand

Now, Some Brief Case Studies

Sweden

Click to Expand

Now, Some Brief Case Studies

France

Click to Expand

Now, Some Brief Case Studies

For a more detailed portrait, see Politico’s Poll of Polls in Europe.

Group Exercise I

Reviewing Far Right Ideology

Golder’s (2016) article begins by mapping the ideological foundations of the European far right party family. This should, in a sense, be a review of material we’ve already covered in class.

Reviewing Far Right Ideology

… and thus, presents an opportunity for another group exercise.

Reviewing Far Right Ideology

Group 1

Juxtapose the extreme right and the radical right: i.e., what brings them together and what sets them apart? Why do “radical” and “extreme” right parties fall under the far right umbrella?

Group 2

Discuss how Golder (2016) links populism, nationalism and fascism

to the European far right party family.

Group 3

Can Golder’s (2016) conceptual model be applied to cases outside Europe?

Moreover, are there elements missing from his definitional framework?

Reviewing Far Right Ideology

We will continue unpacking the “ideology” of Europe’s far right on Wednesday—i.e., by engaging with Mudde’s (2007) canonical work.

Demand Side Explanations

Modernization Grievances

Several studies link far right success to the grievances that arise during the modernization process. The underlying premise in these studies is that there is a small amount of latent support for far right values in all industrial societies. Although this support remains latent under normal conditions, it can be politicized and mobilized during moments of extreme crisis that are related to the modernization process. The typical story is a social-psychological one in which individuals who are unable to cope with rapid and fundamental societal change—the modernization losers—turn to the far right.

(Golder 2016, 482–83, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Modernization Grievances

Scholars home-in on different aspects of modernization theoretically linked to far right ascendancy — including:

Globalization

The Fraying of Social Attachments

The Rise of Post-Materialist Values

Evidence connecting these macrostructural transformations—ignited by modernizing processes—to far right voting has been mixed (Golder 2016).

Economic Grievances

Scholars who link economic grievances to far right success typically do so in the context of realistic conflict theory (Campbell 1965). In times of economic scarcity, social groups with conflicting material interests compete over limited resources. Under these conditions, members of the ingroup are apt to blame the outgroup for economic problems, engendering prejudice and discrimination. Far right parties can exploit these economic grievances by linking immigrants and minorities to economic hardship through slogans such as “Eliminate Unemployment: Stop Immigration.”

(Golder 2016, 483, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Economic Grievances

There is considerable evidence in support of the economic grievance story at the individual level. The characteristics of the typical far right voter … describe an individual who is likely to find himself competing with immigrants in the economic sphere. Such individuals are also associated with holding stronger anti-immigrant attitudes.

(Golder 2016, 484, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Economic Grievances

Yet, “the evidence linking far right support to the economic context in which individuals form their preferences is more mixed” (Golder 2016, 484).

A Question

Why?

That is, why are ecological and individual-level associations between macroeconomic indicators and far right voting highly contingent?

Cultural Grievances

Scholars who link cultural grievances to far right success typically do so in the context of social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner 1979). At its core, social identity theory assumes that individuals have a natural tendency to associate with similar individuals, and that an inherent desire for self-esteem causes people to perceive their ingroup as superior to outgroups. Far right parties are able to exploit and encourage these natural tendencies by highlighting the (alleged) incompatibility of immigrant behavioral norms and cultural values with those of the native population.

(Golder 2016, 485, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Cultural Grievances

There is strong support for the cultural grievance story at the individual level. Multiple studies have shown that anti-immigrant attitudes are positively related to far right support … This in itself should not be read as support for the cultural grievance story, as anti-immigrant attitudes may be the result of economic, as opposed to cultural, concerns with immigration. Attempts to distinguish between these two possibilities, however, indicate that economic and cultural concerns matter for anti-immigrant attitudes.

(Golder 2016, 485, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Cultural Grievances

As Golder (2016) posits, anti-immigrant attitudes don’t always lead to far right voting. Similarly, the local immigrant context does not always influence radical voting patterns in Europe.

A Question

Why?

Supply Side Explanations

Political Fields, Parties and Entrepreneurs

Supply side explanations for the rising tide of the European far right include—but are certainly not limited to—party organization, winning ideologies, and political opportunity structures.

Political Fields, Parties and Entrepreneurs

Let’s focus on the latter.

Political Opportunity Structures

Political opportunity structures reflect a set of exogenous forces—or environmental constraints—that regulate political movement and strategic pursuits within a specific political field.

Political Opportunity Structures

These exogenous factors include, but are not limited to —

Electoral Rules

Party Competition

The Media

Political Cleavage Structure

Group Exercise II

Comparing Opportunity Structures

In your assigned groups, compare and contrast political opportunity structures in Europe and the U.S. Do you think America’s political field is more or less hospitable to far right politics vis-à-vis Europe’s?

A Note on Political Geography

Spatial Distribution of Radicalism

As Golder (2016, 491) argues, “[m]uch can be learned from the political geography of far right support.”

Consider the 2021 German Elections

Or the 2022 French Presidential Elections

A Reminder

With this in mind, please try to read Prof. Ternullo’s (2024) recent paper before she visits our class on Wednesday.

Lecture II: November 13th

Reminders

Response Memo Deadline

Your seventh response memo—which has to be between 250-400 words and posted on our Moodle Discussion Board—is due by 8:00 PM today …

Unless …

… you attend the first Cummings Lecture tonight!

Reminders

The Cummings Lecture

Title

Place, Polarization, and the Future of America’s Political Divisions

Abstract

Click to Expand or Close

Note: Scroll to read entire abstract.

How does place shape America’s polarized politics? Decades of political-economic transformations have reshaped both the kinds of people and the kinds of places that give their support to the Democratic and Republican Parties, hardening political boundaries along lines of race, class, religion, and context. Working-class, ex-urban, and industrial communities that were once the bedrock of the Democratic Party are now the sites of greatest contestation every election cycle, while the affluent suburbs that once fomented conservative activism in the 1950s and 60s are the sites of greatest growth for the Democratic Party. In this talk, sociologist Stephanie Ternullo (Harvard University) will consider the historical causes and contemporary consequences of these shifts in political geography, and the challenges they present for political representation in American elections, including the November 5th presidential election.

Date and Time

Location

Reminders

Final Paper Proposal

Final Paper Proposal Deadline

Your final paper proposals are due by 8:00 PM on Friday, November 22nd.

Reminders

Final Paper Proposal

Guidelines for the final paper proposal can be found here.

Reminders

Final Paper Proposal

To submit your final paper proposal, click here.

Constructing a Conceptual Framework — by Cas Mudde

The Challenge of Circularity

In defining what is still most often called the “extreme right” party family, one is faced with the problem of circularity: we have to decide on the basis of which post facto criteria we should use to define the various parties, while we need a priori criteria to select the parties that we want to define. In other words, whether we select as representatives of the party family in question the Dutch Lijst Pim Fortuyn (List Pim Fortuyn, LPF) and the Norwegian Fremmskrittpartiet (Progress Party, FRP) or the Italian Movimento Sociale–Fiamma Tricolore (Social Movement– Tricolor Flame, MS-FT) and the German Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (National Democratic Party of Germany, NPD) will have a profound effect on the ideological core that we will find, and thus on the terminology we will employ.

(Mudde 2007, 13, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Challenge of Circularity

Some analytic solutions to this “problem of circularity” include—

Gauging Family Resemblances

Developing Ideal-Types

Finding Prototypes

Isolating the Lowest Common Denominator

Isolating the “Greatest Common Denominator”

The Ideological Core

The European Far Right’s Core

[T]he aim of the minimum definition is to describe the core features of the ideologies of all parties that are generally included in the party family.

(Mudde 2007, 15, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Some Review

A Question

What animates the far right’s ideological core?

The European Far Right’s Core

If one looks at the primary literature of the various political parties generally associated with this party family, as well as the various studies of their ideologies, the core concept is undoubtedly the “nation.” This concept also certainly functions as a “coathanger” for most other ideological features. Consequently, the minimum definition of the party family should be based on the key concept, the nation. The first ideological feature to address, then, is nationalism.

(Mudde 2007, 16, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Nationalism

Well, we’ve grappled with this phenomenon before.

A Question

Group Exercise II

Definitional Debates and a Unified Framework

I will, once again, assign you to groups.

Definitional Debates and a Unified Framework

Group 1

Mudde (2007) argues that nativism is the specific mode or expression of nationalism most relevant for understanding far right politics in Europe. To wit, it serves as the far right’s center of gravity. Why? Do Bonikowski et al. (2021) agree? Here’s a hint.

Group 2

What’s Mudde’s (2007) maximum definition of the European far right party family? Does Mudde’s (2007) definition align with Golder’s (2016)?

Group 3

How does Mudde (2007) conceptualize the populist radical right? Specifically, how does he understand concepts like radical and right?

A Preview

Next Week

We will focus on the far right in other world regions.

Next Week

We Will Also Discuss Mainstream Radicalization

Enjoy the Weekend

References

Note: Scroll to access the entire bibliography